For decades, Silicon Valley has symbolized American leadership in technology. It has been the birthplace of chip design companies, venture-backed innovation, and the digital leap. Yet the geography of semiconductor production tells a different story. Advanced fabs are clustered in Asia, and the U.S. has become heavily dependent on overseas capacity. As the nation invests billions in reshoring, the focus is shifting from a single region to a network of regional hubs. Erik Hosler, who recognizes the importance of distributed innovation, underscores that the future of U.S. competitiveness depends on expanding beyond Silicon Valley. His perspective reflects the growing consensus that resilience requires a broader national map of production.

This transformation is not about replacing California but about complementing it with new centers of excellence. From Arizona’s desert to upstate New York’s industrial corridors, regional hubs are emerging as anchors of the semiconductor ecosystem. Federal incentives and private investments are aligning to create clusters that combine research, workforce development, and advanced manufacturing. These hubs are not only reshaping the industry but also redefining the geography of American innovation.

Why Regional Hubs Matter

A resilient semiconductor strategy cannot rely on one location. The concentration of talent and capital in Silicon Valley has produced remarkable breakthroughs, but it has also created bottlenecks. Land costs, housing shortages, and limited manufacturing infrastructure constrain expansion. By fostering regional hubs, the U.S. can diversify risks and distribute opportunities.

Regional hubs also anchor local economies. Each new fab or packaging facility generates thousands of direct jobs and many more in supply chains. These economic multipliers strengthen communities while reinforcing national competitiveness. A diversified geography reduces vulnerability to disruptions and builds a more balanced innovation ecosystem.

Examples of Emerging Hubs

Several states have already positioned themselves as leaders in the next phase of U.S. semiconductor growth. Arizona has attracted major investments from TSMC and Intel, making it one of the fastest-growing hubs for advanced fabs. Texas has drawn commitments from Samsung and other firms, reinforcing its role as a semiconductor powerhouse. New York is emerging as a leader in memory and packaging, with Micron’s investment in Syracuse signaling long-term potential.

These hubs reflect a deliberate effort to balance capacity across regions. Each site builds on local strengths such as access to power, water, universities, or favorable tax incentives. Collectively, they create a network that can compete with global clusters in Asia and Europe.

Building Clusters for Innovation

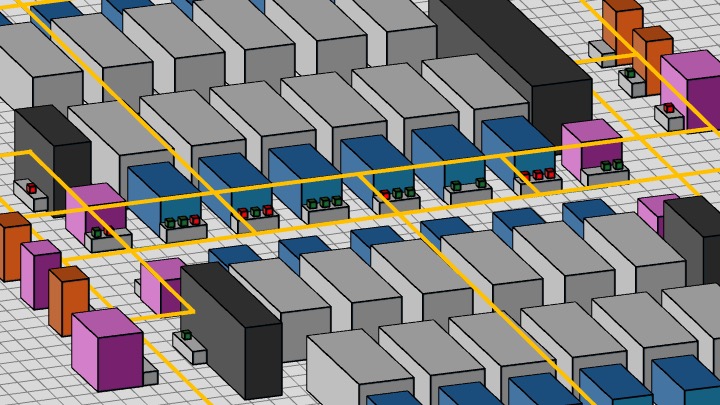

Manufacturing hubs are most effective when they develop into clusters that integrate research, design, and workforce development. A fab by itself is significant, but a cluster creates self-sustaining momentum. Suppliers, universities, and startups gravitate toward these ecosystems, creating feedback loops of innovation.

Silicon Valley succeeded because of these dynamics, and the challenge now is to replicate them nationally. Regional hubs must go beyond hosting factories. They must cultivate talent, research institutions, and support industries that make growth durable. Building clusters requires long-term planning and sustained investment, but the payoff is a resilient foundation for innovation.

Workforce as the Foundation

A regional hub cannot thrive without a skilled workforce. Each fab requires engineers, technicians, and specialists who are in short supply across the U.S. Workforce pipelines must therefore align with regional investments. Partnerships with universities, community colleges, and vocational institutes are essential to ensure that new facilities have the people needed to operate them.

Workforce development also anchors hubs in their communities. When local students see pathways into high-skilled, high-paying jobs, the ecosystem becomes more inclusive and sustainable. By tying opportunity to place, hubs can retain talent that might otherwise migrate to traditional centers like California.

Innovation and Society

The expansion of regional hubs is not only about technology. It is also about shaping the society that surrounds it. Erik Hosler emphasizes, “It must impact society at large. The value of the computations it performs exceeds the cost to build and operate the computer.” His perspective reinforces that manufacturing hubs must generate value beyond fabs, touching education, economic development, and community resilience.

This insight aligns with the idea that technological leadership is inseparable from societal impact. A hub that produces chips but neglects workforce inclusion or community investment risks falling short of its potential. By ensuring that hubs strengthen the regions around them, the U.S. can create durable ecosystems that benefit both industry and society.

Policy as a Driver of Growth

Federal initiatives such as the CHIPS and Science Act provide the incentives needed to attract investment, but state and local governments also play crucial roles. Tax policies, infrastructure development, and education funding determine whether hubs succeed or struggle. Coordination across levels of government ensures that investments translate into lasting competitiveness.

Public–private partnerships amplify these effects. Universities conducting basic research can partner with companies scaling production. Industry and government can co-fund workforce programs. These collaborations provide the stability needed for hubs to grow from projects into permanent clusters of innovation.

The Global Dimension

The U.S. is not alone in fostering regional hubs. Europe and Asia are also investing heavily in distributed clusters to reduce vulnerabilities and capture growth. Global competition ensures that hubs must deliver not only capacity but also excellence. The U.S. cannot afford complacency. It must ensure that its hubs integrate seamlessly with global supply chains while retaining security and resilience.

Allied collaboration strengthens these efforts. Partnerships with Japan, South Korea, and the Netherlands provide access to equipment, materials, and expertise. By combining domestic hubs with international cooperation, the U.S. can position itself as the anchor of a secure and innovative global semiconductor network.

Redefining the Geography of Innovation

The story of American technology leadership is no longer confined to Silicon Valley. New hubs are rising, each carrying the potential to redefine how the U.S. competes in the semiconductor era. From Arizona to New York, regional clusters are becoming the foundation of resilience, spreading opportunity while strengthening national security.

This development requires more than money. It requires vision, workforce pipelines, and policy alignment. By investing in hubs that combine technology with community impact, the U.S. can build a semiconductor ecosystem that is both resilient and inclusive. The geography of innovation is changing, and with it, the future of American leadership.